|

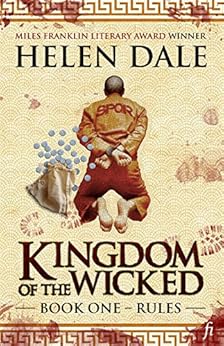

| Amazon link |

I should say 784 ab urbe condita: it seems unlikely that Christianity is going to end up on top when the Roman army is driving around Jerusalem in armoured cars, toting assault rifles. And where a certain Yeshua Ben Yusuf will be on trial for terrorism.

Helen Dale explains her thinking:

"What struck me at once was the attack on the moneychangers in the Jerusalem Temple. All four Gospels record it, and their combined accounts do not reflect well on the perpetrator’s character.Jesus was far from 'meek and mild'.

Jesus went in armed (with a whip) and trashed the place, stampeding animals, destroying property and assaulting people. He also did it during or just before Passover, when the Temple precinct would have been packed to capacity with tourists, pilgrims, and religious officials.

I live in Edinburgh, a city that has many large festivals - religious and secular. The thought of what would happen if someone behaved similarly in Princes Street during Hogmanay filled my mind’s eye. This was not a small incident.

It seemed obvious to me that Jesus was executed because he started a riot. Everything else - the Messianic claims, giving Pilate attitude at trial, verbal jousting with Jewish religious leaders - was by the by.

Our system would send someone down for a decent stretch if they did something similar; the Romans were not alone in developing concepts of ‘breach of the peace’, ‘assault’ or ‘malicious mischief’. Those things exist at common law, too. ..."

"Finally, instead of bringing Jesus forward in time and placing him in modernity, I thought to leave him where he was and instead put modernity into the past. What, I wondered, would have happened had Jesus emerged in a Roman Empire that had gone through an industrial revolution?Of course, new technologies can be introduced under slavery, although without the dynamism which capitalist competition alone provides.

"Other things being equal, what would modern science and technology do to a society with very different values from our own? Would they react with the same incomprehension that we do when confronted by religious terrorism? ..."

"My industrial revolution has its origins when Archimedes survives the Siege of Syracuse in 212 BC and is treated to a Roman version of ‘Operation Paperclip’ (the American retrieval of scientists from defeated Nazi Germany). As a consequence he (or his students) develop calculus and a variety of practical military technologies. In keeping with Roman militarism, the first place the new technologies manifest themselves is in warfare. They then propagate...."

"Chattel slavery undermines incentives to develop labour-saving devices because human labour power never loses its comparative advantage. People can just go out and buy another slave to do that labour-intensive job. Among other things, the industrial revolution in Britain depended on the presence (relative to other countries) of high wages, thus making the development of labour-saving devices worthwhile. ...In the novel, slavery has recently been abolished. And now we turn to Jesus's trial itself.

"Slavery—and its near relative, serfdom—have been pervasive in even sophisticated human societies, and campaigns for abolition few and far between. We forget that our view that slavery and slavers are obnoxious is of recent vintage. In days gone by, people who made fortunes in the slave trade were held in the highest esteem and sat on our great councils of state.

This truism is reflected in history: The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade met for the first time in 1787. It had just twelve members—nine Quakers and three Anglicans. And yet, in 1807, Parliament passed An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

The Quaker role in abolition was so vast it is difficult to overestimate. And in the context of both Christianity specifically and human religion more generally, the Religious Society of Friends is theologically distinct. Who in antiquity could perform the Quakers’ role?

In the end, I lit upon the Stoics, and came to admire many aspects of their philosophy when researching Kingdom of the Wicked. ... "

"I have, however, gestured towards three characteristics of Roman law that set it apart from common law. First is the capacity of judges to investigate matters on their own motion. This explains why Pilate is able to source evidence independent of counsel, something considered most improper at common law.I've just started the book: it's well-written and taut. We're centred around the Roman administration (central characters Pilate, his family and hangers-on) and the Sanhedrin (major figure the high priest, Joseph Caiaphas).

Next is the importance Cornelius [the prosecutor] attaches to obtaining a confession, and the lack of procedural safeguards for the accused. To a Roman lawyer, a confession is the ‘Queen of Proofs’, while his common-law counterpart always suspects that confessions come about thanks to the judicious application of lengths of rubber hose.

Finally, there is the absence of a rule against hearsay, something that is peculiar to the common law."

The Romans are pious yet decadent, hedonistic and sexually uninhibited. The Jews (indistinguishable at the time from their fellow Arab tribes) are socially conservative and sexually repressed, disgusted at the loose ways of their autocratic rulers, the eponymous Kingdom of the Wicked.

Judaea is a hotbed of unrest. Terrorist groups vye with each other in atrocities. There are roadside bombs. And riots.

---

Could capitalism have taken root in Imperial Rome? Marx reminds us that capitalism was never pre-planned as a new mode of production. It took root and expanded where and when it could, and only afterwards was it understood for what it was.

The preconditions for capitalism to emerge seem to be a money economy (which the Romans had) and a strong guild-artisan sector capable of commodity production. At a certain point guild-restrictions on employment of labour are lifted, and the owners of capital begin to accumulate and expand their wealth and power.

They do however need to acquire free labourers, those who have no choice but to work in the nascent factories. In this they compete with landowners who own slaves or control a tied peasantry. The expulsion of landless labourers from agriculture everywhere propelled industrial revolutions.

It is not clear that the proto-bourgeoisie (which barely existed in Roman times) had, at any point, the political or economic clout to seriously contend with the land-owning classes. But it's a complex analysis.

---

My brother notes: "Am surprised that you didn’t include some backstory on [author] Helen Demidenko/Darville/Dale. Her biography is as interesting and extraordinarily as her fiction by all accounts!"

---

Here is the review of "Kingdom of the Wicked Book Two: Order".

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Keep it polite and no gratuitous links to your business website - we're not a billboard here.